Crypto Carbon Credits provides a solution to the wrong problem

Crypto – often used as an umbrella term that encompasses everything that is cryptocurrency – has received considerable and polarizing attention in the last decade. Industry leaders have now entered the carbon trading market claims that taking these markets into the blockchain can result in major gains in environmentally friendly business approaches. But skeptics are unsure of what the cryptocurrency problem is trying to solve, and whether it will succeed in providing energy to the carbon credit market when countries crash towards net-zero targets.

–

What are carbon credits?

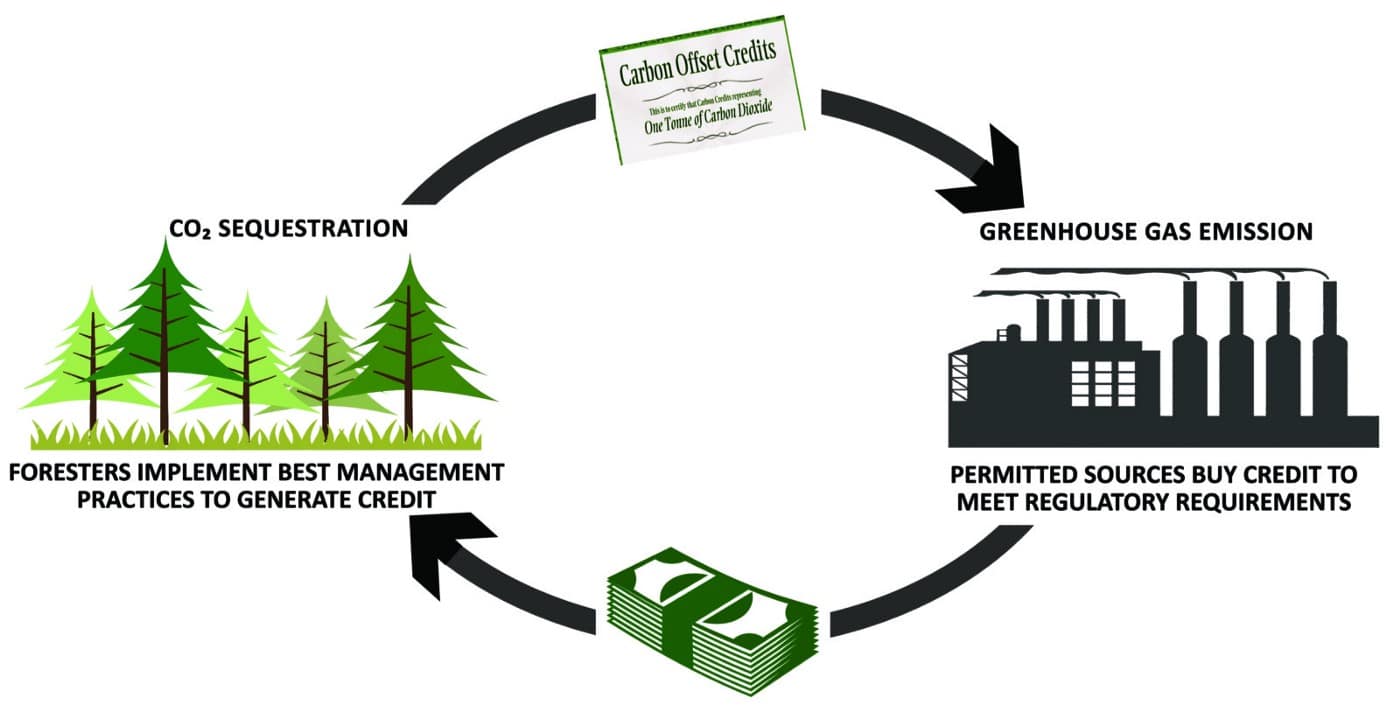

The carbon trade – or carbon market – was first developed and introduced in the 1990s. By allocating a cost to the environmental damage of CO2 emissions, companies can in theory track and compensate their own emissions. By buying carbon credits related to “green projects” on the market, companies across a number of industries can continue their practices while compensating for emissions and thus reducing environmental damage.

For example, a mining company that is subject to an emission limit may purchase an offset credit owned by a forest owner who may agree to use the money to postpone or reduce a harvest. This will then make it possible for the mining company to pollute above the set limit, and use the avoided forest emissions as credit.

Figure 1: The mechanism of carbon offsets

Now, almost three decades after the introduction of the carbon market, decision-makers and activists are unsure of its success. The market remains largely unregulated and discussions are often centered around which projects are considered inclusion. In fact, more Recent studies has emphasized that the associated projects are often overestimated or have little or no positive impact on the environment. In fact, a study of California forest carbon compensation (worth more than $ 2 billion, and the largest program in the United States) found that nearly a third of all offsets were over-credited. In total, this amounted to almost 30 million tonnes of extra CO2 emissions.

You may also like: What are carbon credits and how do they work?

This problem of over-credit has frustrated critics of the carbon market. A combination of a lack of transparency and a systematic error in the way these credits are calculated has ensured that projects continuously miscalculate both pollution emissions and saved emissions.

If we take the study of California as an example, there are often big misconceptions about what constitutes an environmentally friendly offset project. The vast majority of these projects do not involve the growth of new forests as is often assumed, but are instead devoted to the development of practices known as “Improved forest management” (IFM), which are significantly more incremental in the environmental benefits. Only this one example highlights some of the problems with carbon markets and their often exaggerated utility.

Double count – a term that refers to a situation where two separate parties require the same carbon removal project or credit – has also emerged as a problem with the current carbon market. This is really a significant problem and has highlighted the gap between theory and practice for carbon markets. So how does this happen?

Most often, double counting occurs when both the organization that compensates for the emissions and the host country for the project that aims to achieve the climate goals below The Paris Agreement claim the credits. This is obviously problematic: both a country and a company claim to be carbon neutral and yet, when it comes to emission reductions, nothing has actually been achieved. In addition to the immediate environmental effects, double counting also prevents countries from taking action to achieve long-term climate goals.

How does crypto fit into carbon markets?

Crypto supporters believe that a solution lies in this carbon marketplace. Industry leaders have argued that the traditional carbon market is outdated, disorganized and often lacks incentives. They suggest that by moving carbon credits to the blockchain – a digital and open database – cryptoeconomics can motivate companies to adopt more environmentally friendly approaches.

In addition, crypto traders claim that if more people became involved in cryptocurrency credits, this would increase the price of credits. By doing so, they hope to force companies to pay higher prices for emission reductions or drive them to invest in more energy-efficient business practices.

The starting method from the crypto industry was to ‘sweep the floor’. This involved using a bridging process to buy carbon credits that were already circulating in the conventional market and migrate them to the blockchain, at which point a token would be issued to the owner. These tokens can then serve as tradable objects through which blockchain trading can take place. Although supporters of such a transfer to the blockchain often link their mission to environmental goals, there is a clear financial incentive for the transfer. In the current marketplace, the price of carbon offsets has traded in the area at US $ 1-2, while the virtual tokens reached a peak price of around US $ 3000; clear profits for those involved.

While in theory, open-access blockchain technology provides increased transparency, an analysis of some of the first issued cryptocurrency credits revealed two striking findings. The first was that a significant number of ‘zombie’ projects – projects that were not active before the financial incentives generated by cryptocurrency were generated – had appeared on the blockchain. The second was that almost all the credits that had been migrated to the blockchain came from projects that were originally excluded from the current carbon market due to concerns about the quality of the project. So what do these two findings mean for climate change?

What are the weaknesses of Crypto Carbon Credits?

The appearance of “zombie” projects can initially sound positive. In theory, more carbon offset projects should lead to a reduction in emissions. But often, if these loans do not find buyers in the traditional carbon market, it is because buyers had concerns about the quality of the projects in the first place. Migrating these credits to the blockchain does not address these concerns. Instead, previously unsaleable credits and projects are simply used to generate revenue for the owners who “swept the floor” instead of generating new, exciting projects with real potential. But these projects are not the only concern.

The Paris Agreement included regulations for the carbon market in the rules of trade The Clean Development Mechanism under Article 12, which prohibits trading in credits before January 2013. This is to ensure that any new carbon compensation claims are in line with revised standards. However, a dizzying one 84.8% of crypto Carbon credits traded would not have complied with the Paris Agreement rules since they were registered before 2013. In short, cryptocurrency credits appear to be trading projects that would not have found buyers in the conventional markets. By doing so, this technology only serves to reinforce existing structural problems in the current carbon market, while avoiding regulatory standards that are in place under the Paris Agreement.

Crypto supporters argue that the benefit of migrating to the blockchain would be to tackle an outdated, opaque and disorganized carbon market. By doing so, they hope to either increase the price of carbon emissions or force companies to search for more energy-efficient methods. While it is true that the price may have been driven up for some credits, these seem to have benefited the owners of the credits; while the environmental benefits of this practice are either insignificant or in some cases even worse.

But if crypto is not the answer to the carbon market’s problems, then what is?

Can we fix the current carbon market without crypto?

To address the significant issue of double counting, adjusting the national emission targets in Article 12 was a good first step. This meant implementing a policy for the highly controversial “corresponding adjustments”. These adjustments mean that the CO2 emissions that are reduced or removed by the outrigger will be deducted from the project country’s greenhouse gas inventory. This mechanism ensures that for every carbon credit purchased on the market, only one country requires the emission reduction.

Ultimately, the biggest problem is with carbon credits lack of one quality standard. This means that there is a high probability that many sub-optimal projects will end up being priced and sold even if there is no benefit to the environment. If the markets want to be serious about climate change, they must move away from the financing of small, individual projects and towards paying whole companies and thus whole industries, in order to reduce emissions. Ultimately, crypto encouraged the financing of these smaller, insignificant and often discontinued projects, which is in contrast to solutions proposed by experts.

In order to have one quality standard, a reliable and verifiable measure of emission reduction must be in place. By targeting individual companies and then industries as a whole, both voluntary and compensated markets can be improved as the world aims for a low-carbon future.

You may also like: How tokenized carbon credits can help promote climate solutions